A Nature More Resilient

In this piece for the Climate Cultures ‘Environmental Keywords’ project Susan Holliday explores the nature of resilience.

As a community of beings we are in effect all aspects of one indivisible skin, which needs to be strong enough to protect and sensitive enough to feel

Ralph tells me he has come to therapy to learn how to be more resilient. His broad frame perches awkwardly, as though the softness of the chair threatens to emasculate him. Arms heavy with a calligraphy of tattoos - serpents, skulls, a bird of prey - every inch of his body communicates toughness. Only his eyes give him away. His look is haunted, as though a ghost stalks through the inner chambers of his being.

The record company Ralph works for operates in a competitive market. Its staff are rewarded for high-octane performance and long hours. Like his colleagues, Ralph works hard and plays hard. In recent months his sleep has been disturbed by night terrors, which can no longer be assuaged through drinking. He feels he has reached a breaking point. Ralph blames himself for not being tougher. This brings us to the heart of the matter, for Ralph is always trying to be tougher. The only alternative he can see is to being tough is to give in to being weak.

‘What might it look like to be more resilient?’ I ask. Perplexed by the question, Ralph replies ‘I’d be able take the heat, like everyone else.’ I feel him bristle with irritation. He wants solutions from me, not daft questions. ‘How do you take the heat at the moment?’ I persist. Looking me straight in the eye he replies, ‘I just keep going. I try harder.’

Ralph is like a moon unable to turn away from the sun. It simply hasn’t occurred to him that there might be a natural limit to the amount of heat he can take. Competition in the marketplace keeps getting hotter. Everyone is stressed. They just have to deal with it. Resilience in this relentlessly ratcheted environment begins to fail. Under the skin, beneath the protective totems of toughness, Ralph is beginning to crack. His intimate anguish unfolds out of sight. The face he presents to the world is indestructible.

Ralph’s tattoos intrigue me. What might these sentinels be guarding, I wonder. What treasure might warrant this level of protection? We begin by exploring the qualities of his shield – tough, hard, impenetrable, deflecting, protecting. Then, looking for the concealed aspect, I suggest we reverse the tattoo qualities (like a negative in the darkroom). Together we begin to discern the inverse faces of his toughness – soft, tender, yielding, revealing, allowing. Risking everything, I ask Ralph if there might be something he secretly wishes to reveal, something he longs to allow, something he might want to feel. His face flushes. He looks away.

Ralph does not show up for his next session. Nor the one after that. I fear I have lost him. To my surprise, he returns the following week carrying a battered old shoe box covered in faded stickers. Opening the lid Ralph shows me a roughly packaged pile of cassette tapes. A secret hoard of songs, written and recorded when he was just fifteen. This is the first time he has opened the box in twenty years.

Ralph recalls the morning he woke to find his father missing from the breakfast table. A neatly written note explained that he had left them to be with a woman he had met the year before at a conference in Germany. Ralph’s mother said his father was ‘a lousy piece of shit’ and they were better off without him. He would get over it. In the months that followed she soldiered on, modelling a kind of stoic fortitude. Bewildered and bereft, Ralph found himself being the ‘man around the house’, looking out for his mother and three sisters. He had to be strong, for all their sakes.

In the concealed safety of his bedroom the tender adolescent survived – for a while. Wrapped around his guitar he wrote songs about anger and fear, about love and loss. Music stopped him dying inside. No one listened. Hollowed out with forbidden grief for his father, Ralph’s emotional world remained hidden. Shameful evidence of his ‘weakness’. Increasingly he found himself in trouble at school. He got into fights and began taking drugs. They helped block out his vulnerability, his yearning, his grief. In the years since then he has walked through life as a shadow artist, toughing it out organising gigs and record deals for musicians with half his raw talent.

Ralph asks me if I would like to hear one of his songs. He has brought an old cassette player. Slowly, tentatively, he presses the red button to ‘play’. A rough and tender voice pierces the space between us. It is shot through with the raw edge of adolescent loss. Ralph observes me intently. He sees that I’m moved. He knows then that something about his expression of vulnerability is good.

Listening to these songs together in the weeks that follow, Ralph and I begin to discern that sensitivity (not weakness) is the hidden aspect which lies on the other side of his armoured strength. In time he is able to acknowledge that he has never stopped loving his father. He misses him every day. Connected once more to the vulnerability of his heart, he is surprised to discover that love is a power. It stirs in him now with a force that feels unbreakable.

*

It seems that ‘toughness’ has become the exclusive aspect to which we aspire. We admire ‘nerves of steel’ and ‘rock-hard determination’. We ‘hammer out’ and ‘battle through’ our problems. We spin the promise that through therapy and mindfulness we can withstand the intolerable ratcheting up of societal stresses. This confounding of resilience with a limitless capacity to absorb pressure masks the structural problems behind so much of our suffering. It locates the cause of our distress in failures of individual resilience. Worse still perhaps, in our quest to mask our vulnerability, to override our sensitivity and ultimately to deny the inconvenient truth of human limitation, we stuff ourselves with things. Mountains of things. This compulsive consumption is costing us the earth.

In her highly influential TED talk ‘The Power of Vulnerability’, Brené Brown challenges the way we understand our relationship to vulnerability, arguing that our sensitivity to feeling lies at the very heart of our ability to survive and to thrive:

“Vulnerability is the birthplace of love, belonging, joy, courage, empathy and creativity. It is the source of hope, empathy, accountability and authenticity.

If we want greater clarity or deeper and more meaningful spiritual lives, vulnerability is the path.

”

Author of The Highly Sensitive Person Elaine Aron suggests that heightened sensitivity manifests in a certain proportion of all higher species, because it is essential for the survival, expression and evolution of the whole group. As a community of beings we are in effect all aspects of one indivisible skin, which needs to be both tough enough to protect and sensitive enough to feel.

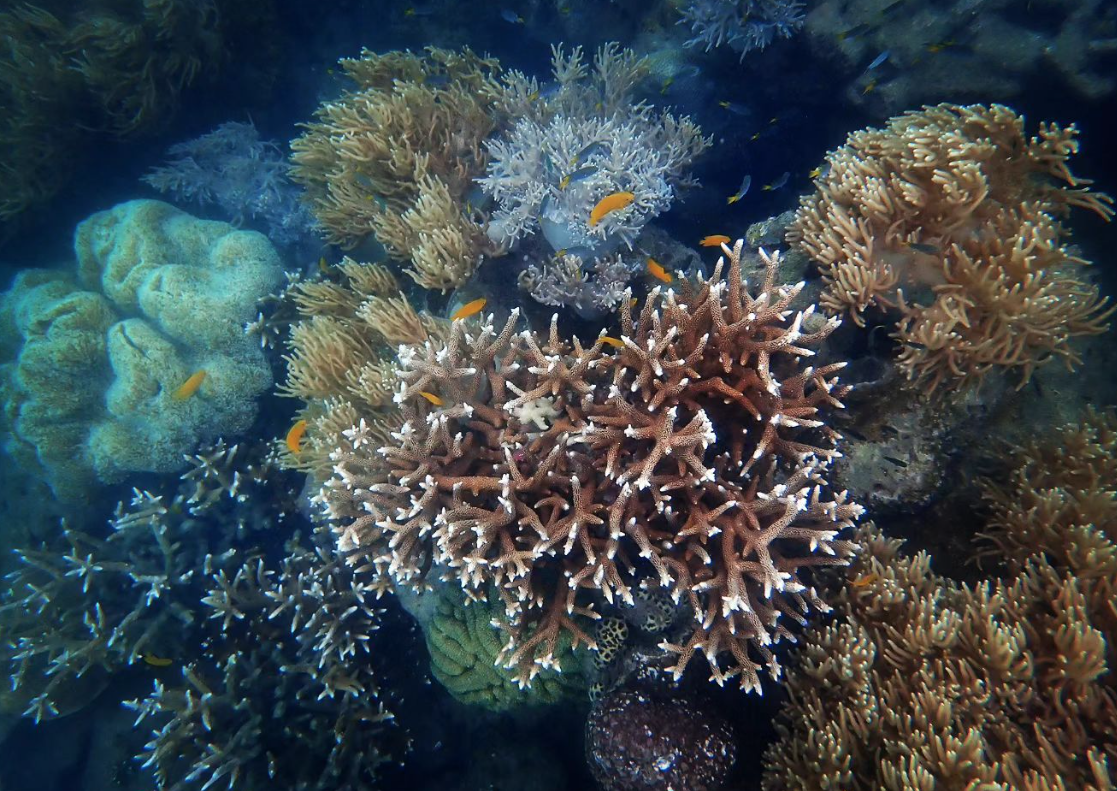

We can see this intimate correlation between sensitivity and toughness throughout the natural world. Reef-building corals for example survive for millennia in a continual cycle of impact and renewal. The living polyps may only be a few years old, but they rely on an underlying skeleton that can live for thousands of years. These corals can adapt to withstand short periods of elevated seawater temperatures. Sensing the warming waters, they expel the microscopic marine algae that live in their tissues exposing the white exoskeleton beneath and losing their vibrant colours. This coral bleaching is a natural process combining sensitivity and strength. It enables the reef to adapt to summer months when the ocean temperatures are warmer.

In recent years sustained marine heatwaves have led to mass coral bleaching events. The Great Barrier Reef, the world’s largest reef system, has already suffered five mass bleaching events since 1998. The events in 2016 and 2017 alone led to the death of 50% of the iconic reef. This unspeakable tragedy points to a condition of nature, concerning which we are increasingly in denial: Nature, including human nature, operates within limits.

Like coral reefs, we too are deformed under excessive stress. The damage begins at the more vulnerable margins, with those of us who are by nature, or through poverty, or by age or youth, more sensitive. But in the end the unbound stresses will affect us all.

Increasingly I see the people who courageously step into the therapy room as equivalents to canaries in the coalmine. Their sensitivity alerts the wider community to psychological toxins and rising temperatures in our collective environment which threaten to overwhelm the balance and limits of resilience in our human ecology as a whole. If we could begin to listen to these more tender voices, rather than medicating them into dumb silence, if we could stop urging people like Ralph to toughen up, we might recover qualities of sensitivity that makes us more resilient as a community.

Could it be that the explosion in mental health problems in people of all ages and backgrounds is not a straightforward failure of individual resilience, but a sign that collective stresses are overwhelming the inherent limits of our shared nature. Ralph’s story reminds us that the waters of our human ecology are overheating. At this point it seems we have two choices. We calcify. Through medication, consumption and addiction we numb the sentient organs of perception that feel. Or we crack, as the colour bleaches out of our lives. The people I worry most about are those who chose to calcify. They are often the ones who head up our corporate organisations and lead our nations. Shorn of their capacity to feel they become a danger to themselves and to others. Increasingly they lead us into war and to the irreparable despoiling of our planet.

Of course, there is a third choice. We could hold the reciprocal qualities of strength and sensitivity in equal regard. We could understand that resilience depends on their intimate correlation.

Brené Brown, Daring Greatly: How the Courage to be Vulnerable Transforms the Way we Live, Love, Parent and Lead (Penguin, 2015)

Elaine Aron, The Highly Sensitive Person (Harper Collins, 2017)

Guest blog written by © Susan Holliday for the Climate Cultures ‘Key Environmental Words’ Project - May 2022

Climate Cultures is an online space for creative minds to share responses to our ecological and climate predicaments. It’s an approach to building creative conversations between and beyond different appreciations of what these predicaments mean, and of what they offer us as ways forward. It’s a beginning.